Bird Photography - Fieldcraft

In the last issue, I discussed the reasons for using a hide and gave some details for building a simple but effective hide. In this feature we will be looking at various ways of ensuring that the birds you wish to photograph are going to appear right in front of your hide.

In the last issue, I discussed the reasons for using a hide and gave some details for building a simple but effective hide. In this feature we will be looking at various ways of ensuring that the birds you wish to photograph are going to appear right in front of your hide.

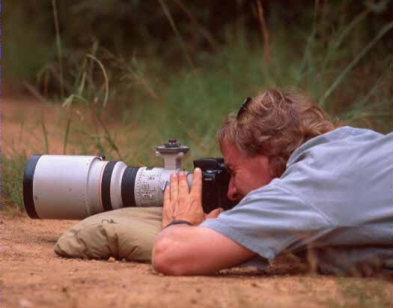

Obviously, to just set up a hide anywhere in the veld and hope that birds appear, is likely to be a long and fruitless exercise. Something is needed to attract birds to the right spot. This can be a natural "hot spot" such as a last remaining pool of water in an otherwise dry area. You can also attract birds to your hide by baiting with food or water. Lastly, you can place your hide near to nesting birds. Nest photography is quite an involved business and there is always the possibility of causing the parents to desert or exposing chicks to predation. I intend to devote an entire feature to the ethics of this topic later in the series. Natural hot spots are my preferred way of getting birds in front of a hide. Providing the right place is chosen, the results are often instantaneous whereas baiting usually requires a period of time before the birds catch on to what is available. Also, very importantly, nothing is done to significantly alter the behaviour or habits of the birds. Natural hot spots can include drinking places and a small pool in a dry area as mentioned earlier is a sure fire winner. Also, regular feeding spots can be productive. These could be a fig tree in fruit (although you may need a pylon platform to get to the bird's level), shallow areas in a dam where waders feed or perhaps a lily margin in an otherwise deep pan which would be sure to attract jacana. Another potential hot spot is a regular roost and I have had good results at high water roosts in tidal estuaries. Regularly used perches are also excellent hide photographic venues. As well as feeding perches such as a branch over a stream used by kingfishers, perches are also utilised for display. Even a small sapling or twig in otherwise featureless highveld grassland will certainly attract displaying widowbirds. It is usually best to set up your hide a few days before intending to photograph so that the birds become completely oblivious to it. The key to successful photography at natural hot spots is to spend time doing some fieldwork first. I wish I had done more looking first before rushing in to photograph when working on my "Waterbirds" book a few years ago. Obviously an African waterbirds book is going to need some pictures of flamingos. I was on a pretty tight budget at the time so unfortunately a trip to the famous East African soda lakes was out of the question. Eventually I located some good concentrations of lesser flamingo on a pan near Delareyville in North West Province. The pan was fairly modest in size and held, at a rough estimate, six thousand flamingos. Great, I thought, this is going to be easy. I set up a couple of hides and returned to the pan very early the next day. What I saw in the predawn light did not look very promising. The flamingos were scattered throughout the pan except around my two hides where there were neat semicircles of about 100m radius of absolutely no flamingos! They did not have to feed in front of my hides so they obviously thought it best to avoid these strange looking box structures. Several fruitless mornings followed and as the birds were clearly wary of the hides, to keep a low profile I even tried lying flat on a sheet of polythene in the mud and pulling a hide canopy over me. This did produce a few photographs plus a nasty crick in my neck. Unfortunately the polythene was only partly effective in keeping out the mud. The mud of saline pans frequented by flamingos is uniquely gooey in texture with an interesting smell about midway between rotten eggs and sewage. No amount of washing seems to remove this and my wife said I smelt horrible for at least the next week! The solution to the problem was only discovered a week later. By chance I thought I should check progress at the pan late one afternoon. The flamingos were still largely avoiding my hides but, interestingly, there was a large concentration of birds around a separate little puddle at the northern tip of the pan. Closer inspection proved this to be a freshwater seep where the flamingos drank and bathed. The following afternoon I set up a hide close to the freshwater seep. I did not have long to wait as within half an hour, a veritable army of flamingos approached. My hide was no longer a problem for them as they badly needed fresh water as a respite from the terribly saline water of the pan. In the next hour or so I got all the pictures I needed for the book and by the end of the afternoon my hide was surrounded by a sea of flamingos. The moral of the story is: take time to identify natural hot spot opportunities before rushing in to photograph! Natural hot spot opportunities do not always present themselves so sometimes the only option is to attract birds to your hide by baiting. The bait used depends of course on the target species. I've had success with wild bird seed, mealies, fruit, suet, strips of meat and fish. It is generally necessary to bait an area for a few days before starting to photograph and baiting tends to be most effective when there is not too much natural food available. Long term baiting is not a good idea as it could make the birds dependent on an artificial food source. In the dry season, baiting with water can also be very effective. A sheet of heavy duty polythene makes a good artificial pond as long as the sides are camouflaged with earth to prevent any polythene showing in the photographs. Lastly, a hide that has been set up for several days could well harbour a snake or a scorpion so it is wise to check carefully before getting inside! Also, because hides can get very hot and stuffy, dehydration is a danger. For this reason, during summer I restrict my hide photography to early morning sessions only. Top | Previous | Next | Tips Home | Stock Images | Books | Tips | Gallery | FAQ's | Kruger Park | Contact Text and photographs © Nigel Dennis |